Consent in health and social care: A practical guide for healthcare professionals

Key Takeaways

- Consent is a conversation, not a tick-box exercise, and it needs to happen throughout every stage of care

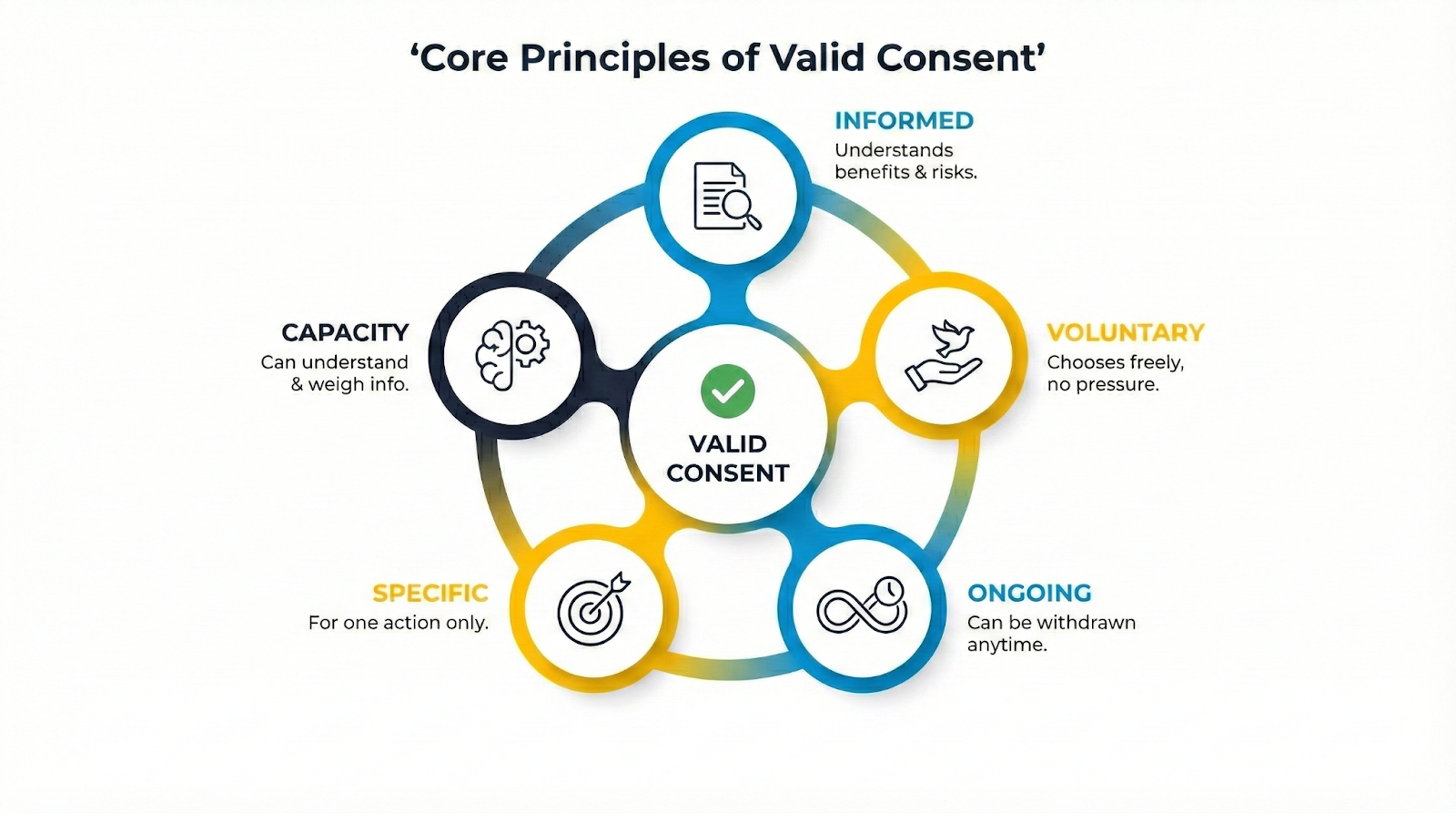

- The five principles that make consent valid are voluntary choice, informed understanding, capacity, being specific to each decision, and being ongoing

- Good consent means understanding first, agreement second, and then documentation to back it all up

- When someone struggles to make a decision, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 sets out how to support them and work in their best interests

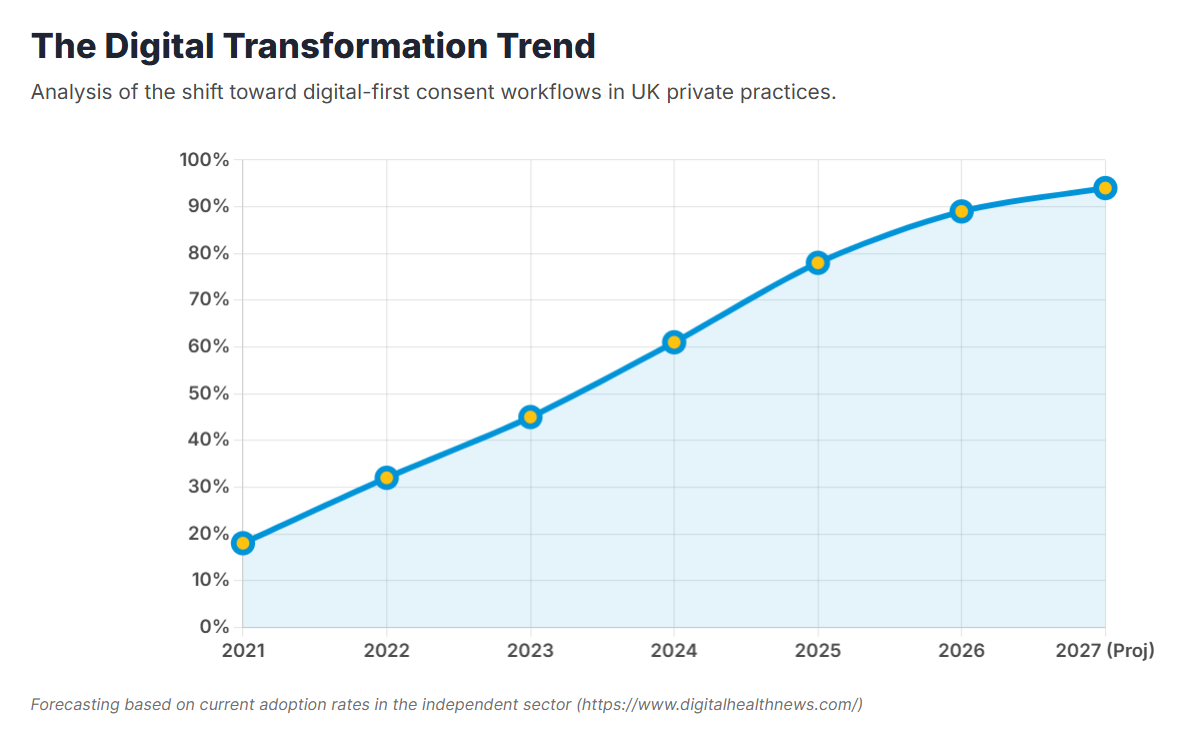

- UK GDPR-compliant systems and digital consent capture help keep your documentation consistent without the admin headache

Consent in health and social care is how you keep people in control of what happens to them. It's a conversation that runs through every stage of care and treatment.

In private practice, consent is also about consistency. When the conversation is clear and the record is solid, care runs smoothly across appointments and settings.

This guide explains what consent means in practice, how to get it right and what to document.

What is consent in health and social care?

Consent in health and social care is a person's voluntary, informed consent to receive care, treatment or support, or to allow their information to be shared. It reflects a fundamental legal and ethical principle: people should have control over what happens to their bodies and their personal information.

The legal baseline is clear. Under Regulation 11, consent to care and treatment must be provided only by the relevant person.

In practice, consent is not a consent form. A consent form can support your records, but cannot replace the conversation. People should be given information in a way they can understand, including relevant risks and alternatives.

Consent should also be specific to the decision in front of you. Agreement to one element of care does not automatically apply to other actions or future sessions. If circumstances change, consent should be checked again and recorded.

The core principles of valid consent

These principles help you check whether consent is valid before you move ahead:

- Voluntary: The person is choosing freely, without pressure from professionals, family, friends or circumstances.

- Informed: They understand benefits, relevant risks, possible complications, realistic alternatives and what happens if they decline.

- Capacity: They can understand, use and weigh the information for this decision and communicate their choice.

- Specific: Consent for one action does not automatically cover other actions or future decisions.

- Ongoing: Consent can be withheld or withdrawn at any time and should be revisited if the plan changes.

If one principle is missing, slow down and reset the conversation.

Types of consent with simple examples

Different situations call for different ways to confirm consent. The standard for validity stays the same.

- Implied consent: A person's actions clearly indicate agreement for routine, low-risk care, such as offering an arm for a blood pressure check.

- Verbal consent: A clear yes after discussion, such as agreeing to a treatment decision during a consultation.

- Written consent: Confirmation in writing where decisions are higher risk, more complex or where policies and procedures require a written record.

Implied or non-verbal consent can be appropriate in routine settings, but only where the person understands what is happening and has a real choice.

How to establish consent in health and social care

Getting consent right comes down to a workflow you can repeat, without turning the conversation into a script. Most problems happen when consent is rushed, assumed or documented too lightly.

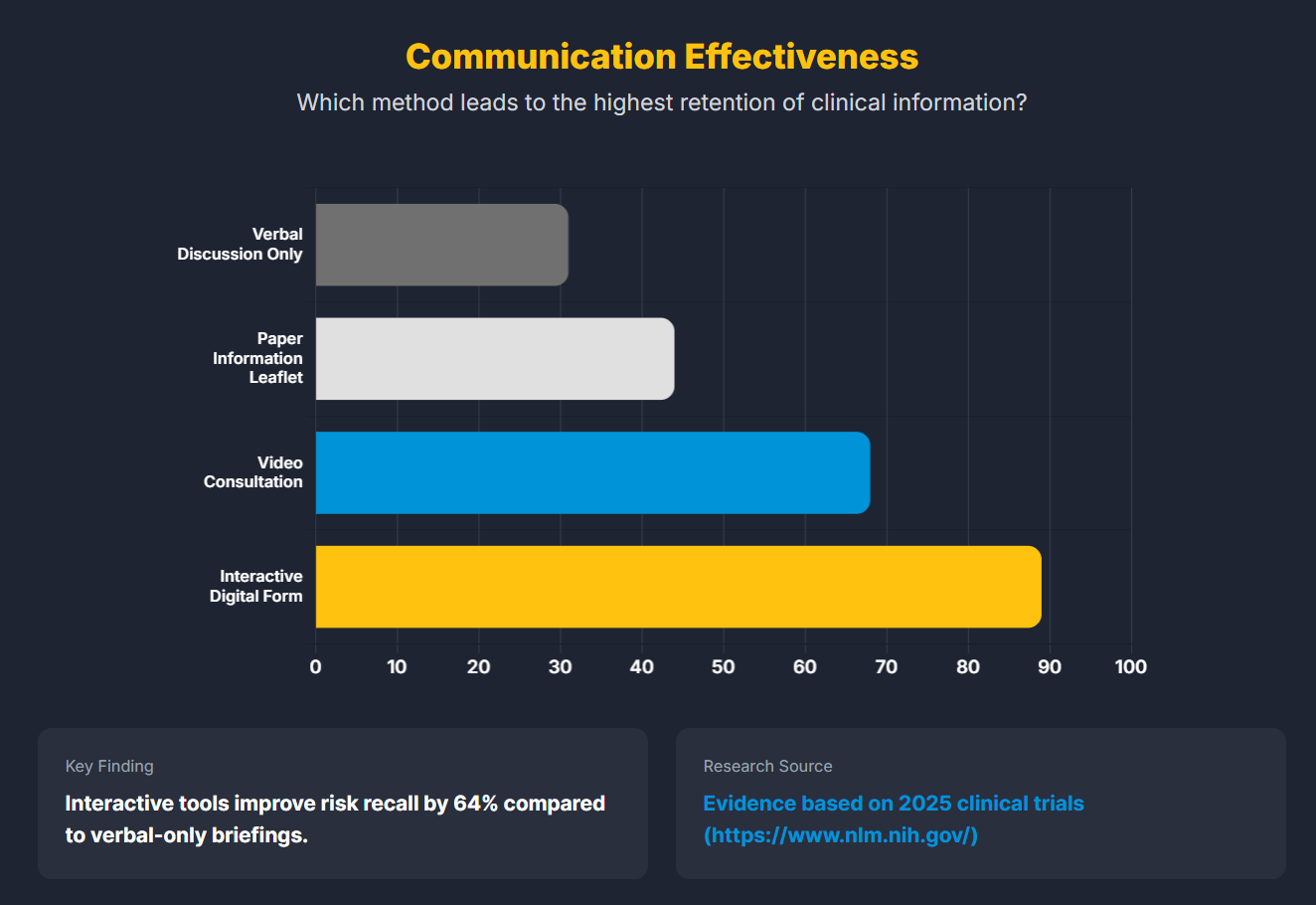

CQC's guidance on consent focuses on practical standards: provide information in a way the person can understand, include relevant risks and alternatives, and make sure the person seeking consent can answer questions. The goal is shared decision-making where understanding comes first, agreement second, and documentation third.

A practical consent workflow:

- Explain what you're proposing in plain language. Start with what you plan to do and why.

- Cover benefits, risks and realistic alternatives. Keep it specific to the person and the decision.

- Check understanding. Ask the person to summarise the key points back in their own words.

- Confirm the choice is voluntary. Give space for questions and refusal without judgement.

- Confirm capacity when needed. If someone is uncertain or struggling to take in information, adjust how you explain and slow the pace.

- Confirm agreement and next steps. Be clear about what the person is agreeing to.

- Make it easy to change their mind. Consent is ongoing and can be withdrawn at any time.

- Document what matters. Record enough detail to show what was discussed and what was agreed.

Situations that need extra care:

- Communication needs: Adapt the discussion so service users can understand, including accessible formats or appropriate language support.

- Remote consultations: Confirm consent clearly at the start and record it, especially where sensitive information may be discussed. For video consultations, this includes checking the person is in a private space.

- Family involvement: Person-centred care keeps the person at the centre of the conversation and watch for signs of pressure.

- Time pressure or distress: Avoid pushing decisions when the person is rushed or overwhelmed, where a pause or follow-up is safer.

A consistent workflow reduces errors and makes documentation more defensible later.

Capacity, best interests and when consent does not apply

Most consent conversations are straightforward. The tricky cases fall into two areas: when capacity is uncertain, and when legal frameworks change how decisions are made.

Scenario 1: Capacity is uncertain. Capacity is decision-specific, not a label. Start by supporting decision-making before moving to best interests. That can mean breaking information into smaller parts, using written summaries or allowing more time.

If the person cannot make the decision, practice should follow the Mental Capacity Act 2005 framework, including best interests decision-making and involving the person as far as possible.

Scenario 2: A different legal basis applies. Regulation 11 includes provisions for people aged 16 or over who lack capacity, and for those under 16 where parental responsibility applies, and for circumstances where mental health legislation applies. In these situations, consent may not operate as usual, but the rationale still needs to be proportionate and clearly recorded.

When the usual consent process cannot be followed, the record shows what applied, what was considered and why a particular action was necessary.

Documenting consent and avoiding common pitfalls

Documentation is where consent becomes durable. A clear record shows what the person agreed to, what they understood and how the decision was reached.

A practical checklist for documenting consent:

- What was proposed and why

- Risks, complications and alternatives discussed

- How understanding was checked

- Confirmation that the decision was voluntary

- The decision and agreed next steps

- Any refusal or withdrawal and what happened next

- Any capacity concerns and the steps taken

Consent also matters when you share confidential patient information or personal data. The HCPC guidance on consent and confidentiality sets out a simple standard: consent for disclosure is only meaningful when the person understands what will be shared, why, who it will be shared with and how it will be used. Valid consent must be voluntary and informed, and the person must have the capacity to decide.

This is a useful way to apply that in practice:

- Implied consent is more likely to apply when information is shared within a care team for direct clinical care and the person would reasonably expect it.

- Express consent is safer when disclosure is outside direct care, involves third parties or would be unexpected.

If you're unsure whether implied consent applies, treat that uncertainty as a prompt to ask for express consent and record it clearly.

Where things go wrong:

The biggest problems? Assuming silence means yes, using forms as a shortcut instead of having the conversation, or skipping the step where you check someone actually understands. Records fall apart when refusals don't get documented, when you don't adjust how you communicate, or when information gets shared in ways people didn't anticipate.

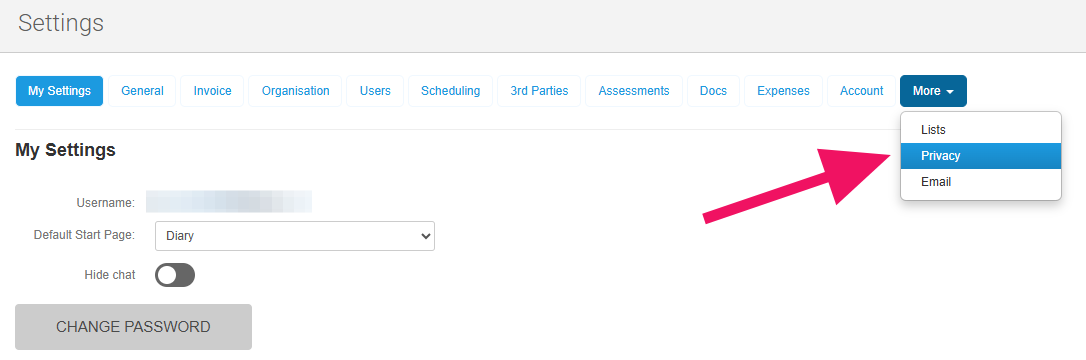

Streamline consent documentation with WriteUpp

Good consent conversations can still end up with patchy documentation. One clinician writes detailed notes, another keeps it brief, and someone else uses a different template. These gaps don't show up until you need to justify a decision months later. Choosing the right practice management system makes a real difference. WriteUpp keeps consent-related information attached to the client record:

- Smart Forms: Send intake forms after online booking, include consent questions and save responses directly to the client record.

- Electronic informed consent: Collect consent responses and signatures digitally alongside clinical notes.

- Templates: Keep consent wording consistent with reusable form and document templates.

- Secure record-keeping: Store records in a UK GDPR-compliant platform designed for healthcare documentation.

Tie it together with a consistent consent workflow

Consent in health and social care is more reliable when treated as a repeatable process, not a one-off task. Explain the proposed care in a way the person can understand, check that their choice is voluntary and revisit consent when circumstances change.

When that process is backed by clear documentation and clinic management software or private practice software designed for healthcare workflows, you protect autonomy and support safer care across every appointment.

Ready to make consent documentation more consistent?

WriteUpp's smart forms and secure record-keeping take the guesswork out of capturing consent. Start your free 30-day trial to see how much smoother your workflow can be.

Join over 50,000 clinicians that we've helped using WriteUpp

Start my free trial

.png)